Underappreciated Research

Removing Stigma From a Hard-Hitting Field

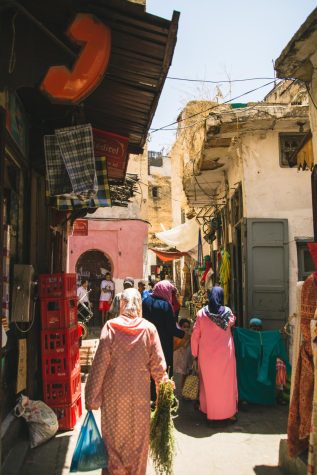

From covering war zones across the globe to local breaking news events, journalists are often faced with the brunt of hardships—often with nowhere to turn to afterwards. After reporting on distressing events, journalists can develop PTSD. Post traumatic stress disorder is nothing new. Soldiers, first responders, and survivors of traumatic events often struggle with it. However, people do not often address the ghosts that reporters face each day after reporting on the field. Some might shrug it off, claiming it is just a part of the job. Others might ignore it entirely. But there are many examples of reporters who take a break for mental health reasons. One journalist shifted his career from breaking news reporting in Phoenix to ministry because of the anxiety that was triggered from reporting on tragic news stories. Covering rapes, deaths, and domestic abuse can take a harsh toll on talented reporters. Journalists are heroes—but it is often heroes who need the most help.

Based out of Africa, BBC reporter and editor Fergal Keane stepped down from his position, citing PTSD as a reason. Keane reported on the Rwandan Genocide in the 1990s and continued to report on different events throughout Africa for many years. He won multiple awards for his coverage in Africa during his time there. As a veteran journalist, he was honest about his struggles with depression and trauma—something many journalists may not share with their peers and superiors. While it seems that most of his comrades were supportive of his decision to step down, it must not have been an easy choice to make after years of service. It takes courage to acknowledge one’s personal limitations and take the necessary step of faith to put your well-being first.

An underappreciated topic is something that is not often addressed by society or talked about frequently. PTSD is often discussed because it is an issue that many people face, whether they face it personally or vicariously through a loved one who has it. The Veterans Affairs reports that 6 out of every 100 people in America will suffer with PTSD at some point in their lifetime. However, it’s not often discussed how reporters are faced with PTSD as their job is one of the most traumatic of career options. Most universities fail to teach their students how to brace for the trauma or steps to take after they are faced with it. Most workplaces do not address the issue until their staff is resigning for mental health reasons. It tends to be a conversation for people that happens after the effect–rather than a preventative dialogue.

The American Psychological Association calls journalists “vicarious first responders.” They often arrive on the scene shortly after the police or fire department, telling the story for others to see and be aware of. They report on victories and tragedies. But because of this, there can be a sense of trauma that affects journalists who are brought face to face with hardships. They don’t often have the same support that other first responders may have.

A piece by Psychology Today also focused on journalists being similar to first responders, in their challenging jobs and in what they deal with afterwards. In a survey asking journalists about PTSD symptoms, Psychology Today reported that “respondents reported heightened anxiety, difficulty sleeping or concentrating, irritability and outbursts, avoiding talking or thinking about the event or visiting places associated with it, hopelessness, detachment, loss of interest, and sadness.” Two of the reasons included in the reasoning of increased PTSD in journalism are that since there are fewer jobs in the field, younger, inexperienced reporters are covering the challenging beats. Another reason is that there is a sense of journalism culture that promotes leaving personal life out of the newsroom, including trauma from the job.

What exactly would qualify as “trauma?” The APA defines trauma as “exposure to or threatened serious injury, or sexual violence” in different ways, from natural disasaters to wars to domestic abuse. According to the Dart Center, 80%-100% of journalists are exposed to work-related trauma throughout their career. Sometimes it is directly related to the job, but sometimes it is personal, like if someone targets the reporter for a story they are covering or how they did.

The competitiveness of the field makes it difficult for reporters to be honest with their peers about their struggles. The Guardian explains journalism as a “field where the competition is intense.” After finally landing a job, many journalists would not admit their struggles for fear of losing their jobs or their beats to others who are vying to enter. Confessing a weakness may end years of hard work. Not only is it competitive, it is not always the easiest. Career Cast conducted a survey in 2012 which said that reporting was the fifth worst job anyone could have. Most reporters might argue differently, but would still admit it is not an easy job.

Poynter featured a story written by Hannah Storm, a journalist who currently writes and speaks on journalism safety and mental health, explains the complexity of the craft: “Relentless breaking stories, a rise in attacks against the press, a crisis of trust, job cuts, sinking ad revenues causing stress, burnout, vicarious trauma, moral injury, and exhaustion have taken their toll on the mental health of individuals and the cultural and economical health of our industry. If we aren’t well, we can’t do our best work.” Storm argues that there are more journalists who struggle with PTSD than let on. Admitting their struggles is the first step needed to finding healing and help, Storm writes.

Symptoms of PTSD include anxiety, depression, night sweats, mood swings, flashbacks and difficulty sleeping. In her personal account, Hannah Storm writes that she tried to self-medicate with antihistamines to stop her nightmares. Everyone deals with PTSD differently. “I’ve seen colleagues self-medicate with drink or drugs, self-sabotage with affairs, bully others, abuse their power, or push themselves to such extremes that their editorial judgment was impaired,” Storm wrote for Poynter. She was diagnosed with C-PTSD, a form of trauma that has taken on multiple forms over her lifetime.

Journalists who suffer with PTSD should be honest about their struggles and seek to find ways toward help and healing. There are many psychologists who study this specific field of trauma and provide counseling for journalists who are looking for help.

While there is this immense focus on how to report on a topic with trauma, there is little training on the personal aftermath. Student journalists are taught what questions to ask in interviews, how far to go, what to write about and what to leave out of articles, but there is little training on how to deal with the trauma after reporting on it. Poynter offers a course called “Journalism and Trauma” which teaches journalists how to report on traumatic events. It is a challenge and should be done with the utmost grace and kindness, but there should be courses for students to learn about personal traumatic help.

The U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs hosts a website that features journalists who have PTSD. There, they also compare the similarity of the trauma to that of a firefighter or an emergency room doctor, both professionals faced with potentially devastating outcomes. The VA explains how most journalists have kept this struggle silent from their peers. “Until recently, journalists felt that if they publicly acknowledged that reporting experiences might affect them long-term, the journalist would be thought of as weak and less capable than his or her colleagues,” the VA reports. Because of this, there has been an underappreciation of this research topic.

Journalists should not fear transparency and honesty—they are, after all, cornerstones of ethical reporting. They must seek healing and care for their hearts and minds after coming face to face with traumatic events that cause PTSD. Just like a police officer, soldier, or firefighter would do, they should find solace in knowing they are not alone. While PTSD may not be fully curable, there are ways to lessen symptoms with therapeutic methods, according to Psychology Today. Removing the stigma from PTSD can help journalists find peace in their own lives and continue to pursue excellence in their professional lives. Bibliography

Brienza, Victoria. “The 10 Worst Jobs of 2012.” CareerCast.com, CareerCast.com, 9 Mar. 2017,

https://www.careercast.com/jobs-rated/10-worst-jobs-2012?page=4.

Clay, Rebecca A. “Journalists as Vicarious First Responders.” American Psychological

Association, American Psychological Association, 17 Apr. 2020, https://www.apa.org/topics/covid-19/journalists-first-responders.

Coelho, Sherwin. “Working in Journalism: What I Wish I’d Learned at University.” The

Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 11 June 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/careers/careers-blog/journalist-job-market.

“Journalism and Trauma.” Poynter, 20 Mar. 2019,

https://www.poynter.org/shop/self-directed-course/journalism-and-trauma/.

Prijatel, Patricia. “Like Other First Responders, Journalists Face PTSD.” Psychology Today, 5

Aug. 2019, https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/all-is-well/201908/other-first-responders-journalists-face-ptsd.

Sherman, Carl. “The Quest to Cure PTSD.” Psychology Today, 14 Oct. 2019,

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/articles/201910/the-quest-cure-ptsd.

Smith, River. “Covering Trauma: Impact on Journalists.” Dart Center, Columbia Journalism

School, 24 Apr. 2019, https://dartcenter.org/content/covering-trauma-impact-on-journalists.

Storm, Hannah. “My Mental Health Journey: How PTSD Gave Me the Strength to Share My

Story .” Poynter, 24 July 2020, https://www.poynter.org/business-work/2020/my-mental-health-journey-how-ptsd-gave-me-the-strength-to-share-my-story/.

“Trauma and Shock.” American Psychological Association, American Psychological

Association, https://www.apa.org/topics/trauma.

“U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs.” How Common Is PTSD in Adults?, 13 Sept. 2018,

https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_adults.asp.